The Third Space:

Japanese American Resettlement in Greater Philadelphia

About the exhibition:

What does it mean to be an internally displaced person in your own country, and where do you go when there is no home left to return to?

Walk through The Third Space with creators Rob Buscher and Bryant Girsch

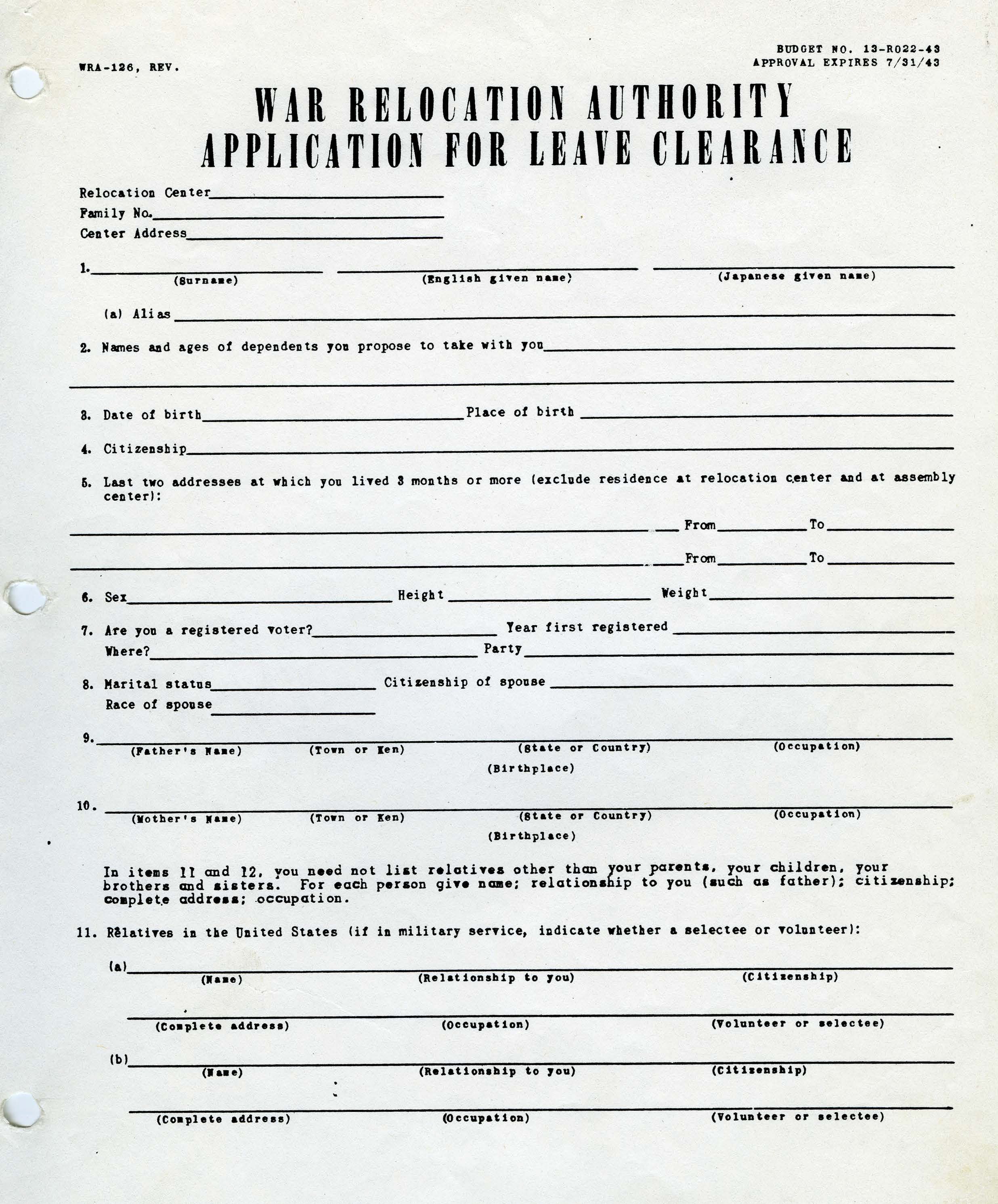

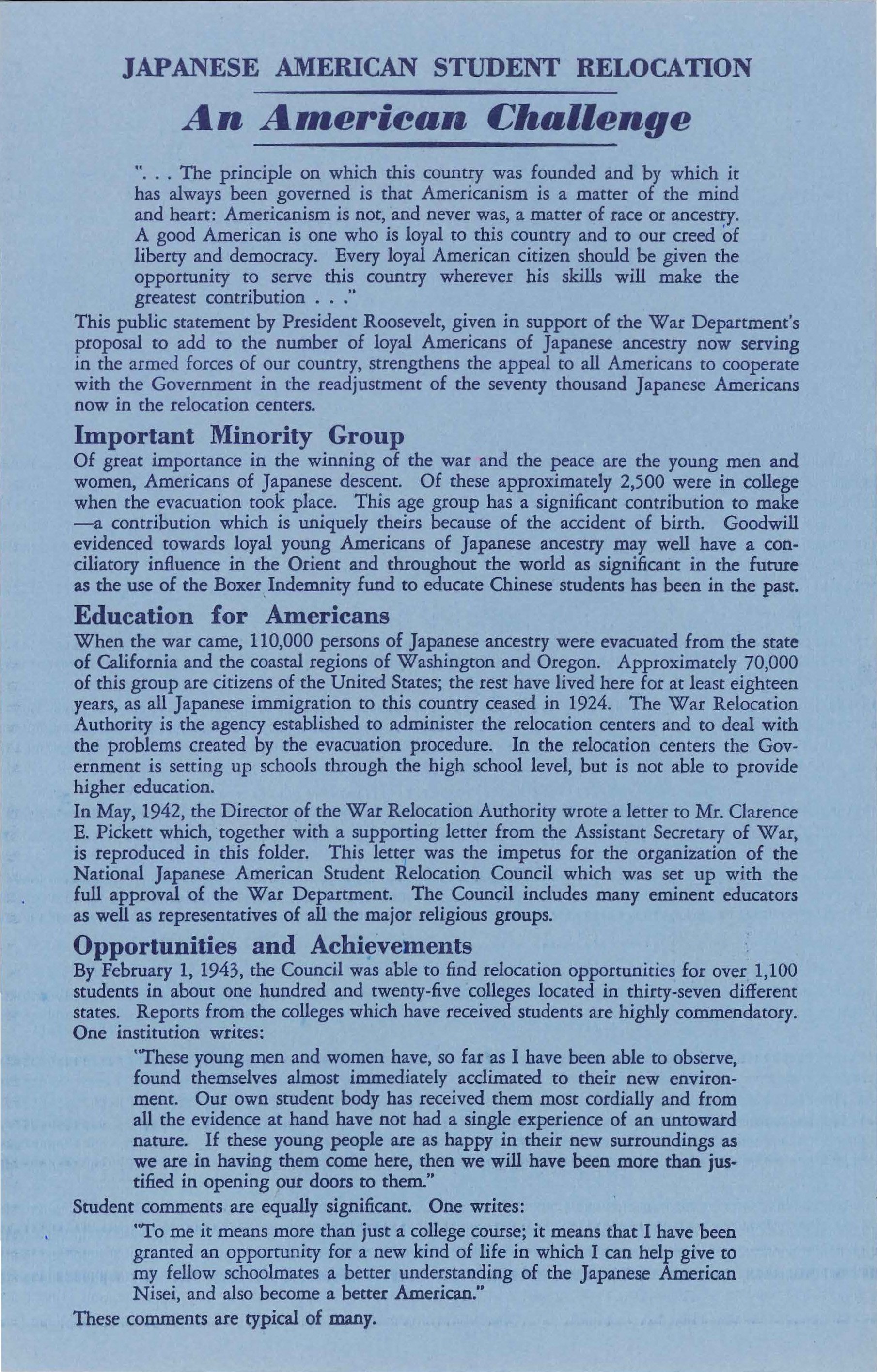

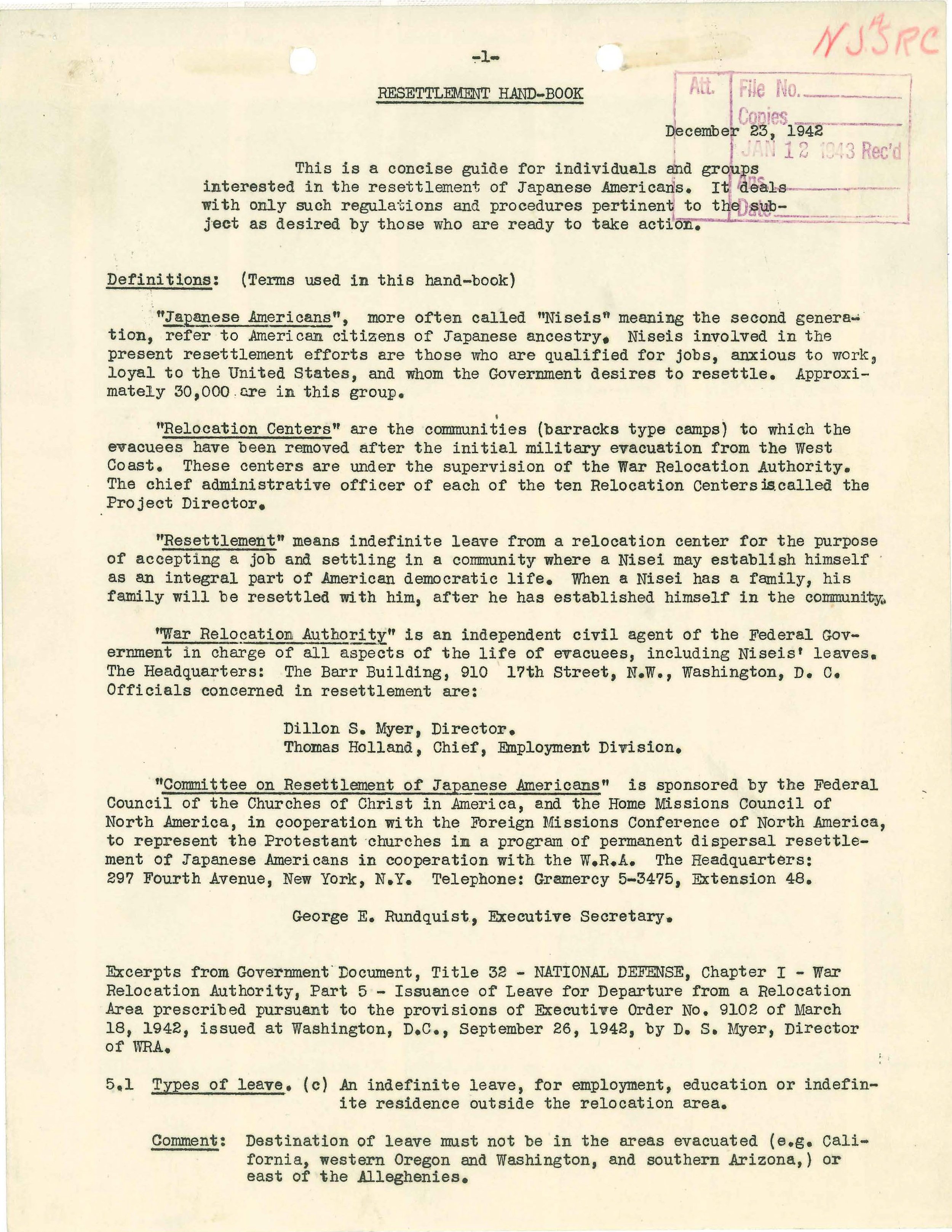

These are questions that many Japanese Americans living in the West Coast of the United States faced in the aftermath of Executive Order 9066, which ultimately led to the forced removal and mass incarceration of more than 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry during the Second World War. While much work has been done to share the experiences of the Japanese Americans who were forced into US concentration camps administered by the War Relocation Authority from 1942 – 1946, far less attention has been given to documenting and sharing the stories of this community as they began to rebuild their lives in the postwar era.

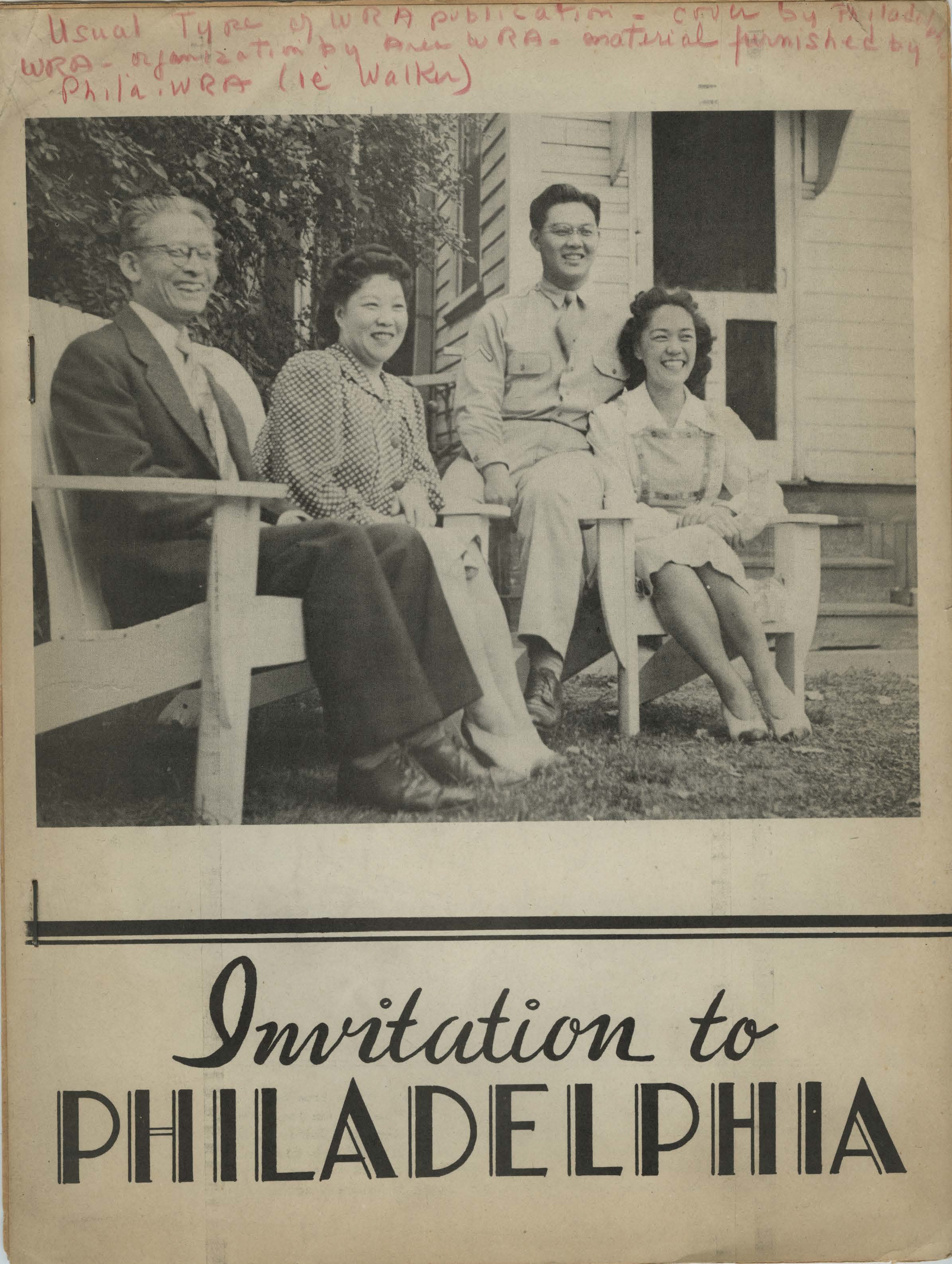

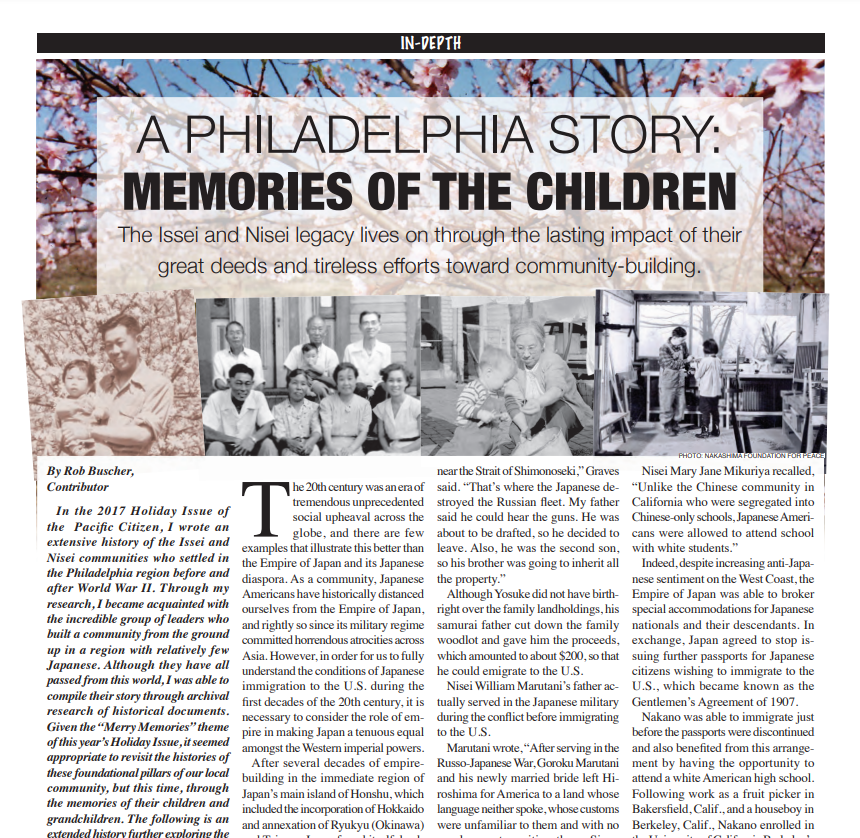

Philadelphia became the first major city on the East Coast to welcome Japanese American students to continue their education at local schools amidst the incarceration of WWII. This paved the way for a significant community of resettlers into the region both during and after the war. The story of resettlement into this region is unique because of the interfaith allyship that created an atmosphere of tolerance for most individuals who resettled here. This was largely due to the advocacy efforts of the Quaker-led American Friends Service Committee headquartered in Philadelphia, but also the Presbyterians and other Pennsylvania-based faith groups. With the aid of Quaker institutions such as Swarthmore and Bryn Mawr Colleges, college-aged Nisei were invited to settle in the Philadelphia region as early as Fall 1942 to resume their studies.

Later as the WRA began large-scale resettlement to the region, a number of unconventional allies presented themselves. The American Federation of Labor Pennsylvania Local 929 Union and Seabrook Farms in nearby Bridgeton, New Jersey opened their farms and factories to the Japanese American laborers whose permanent leave from the WRA camps was conditional on their employment. At its peak the Japanese American community reached nearly 7,000 in the Greater Philadelphia region. Those who settled in the city of Philadelphia and nearby suburbs dispersed almost immediately, with few visible traces beyond JACL chapter convenings and participation in the annual Philadelphia Folk Fair. Inversely, the Japanese Americans who came to live and work on Seabrook Farms were perhaps the only community on the East Coast who closely resembled a Japantown for several decades following the resettlement period.

Although Japanese Americans experienced a fairly positive reception in Greater Philadelphia comparative to other regions of the country, incarceration survivors and their descendants were still traumatized by their wartime experiences. Many were stigmatized from outwardly expressing their Japanese culture and faced intense pressure to assimilate into mainstream American culture from both within and outside the Japanese American community. Despite these factors, the Japanese American communities of Philadelphia and Seabrook found ways to maintain a connection to their Japanese American identity through community organizing and material culture. Art played a particularly important role in both the wartime incarceration and resettlement to Greater Philadelphia as Japanese Americans processed and, in some cases, documented their experiences through photographs and other forms of visual art.

Billy Manbo clutches a barbed wire fence, Photo by Bill Manbo

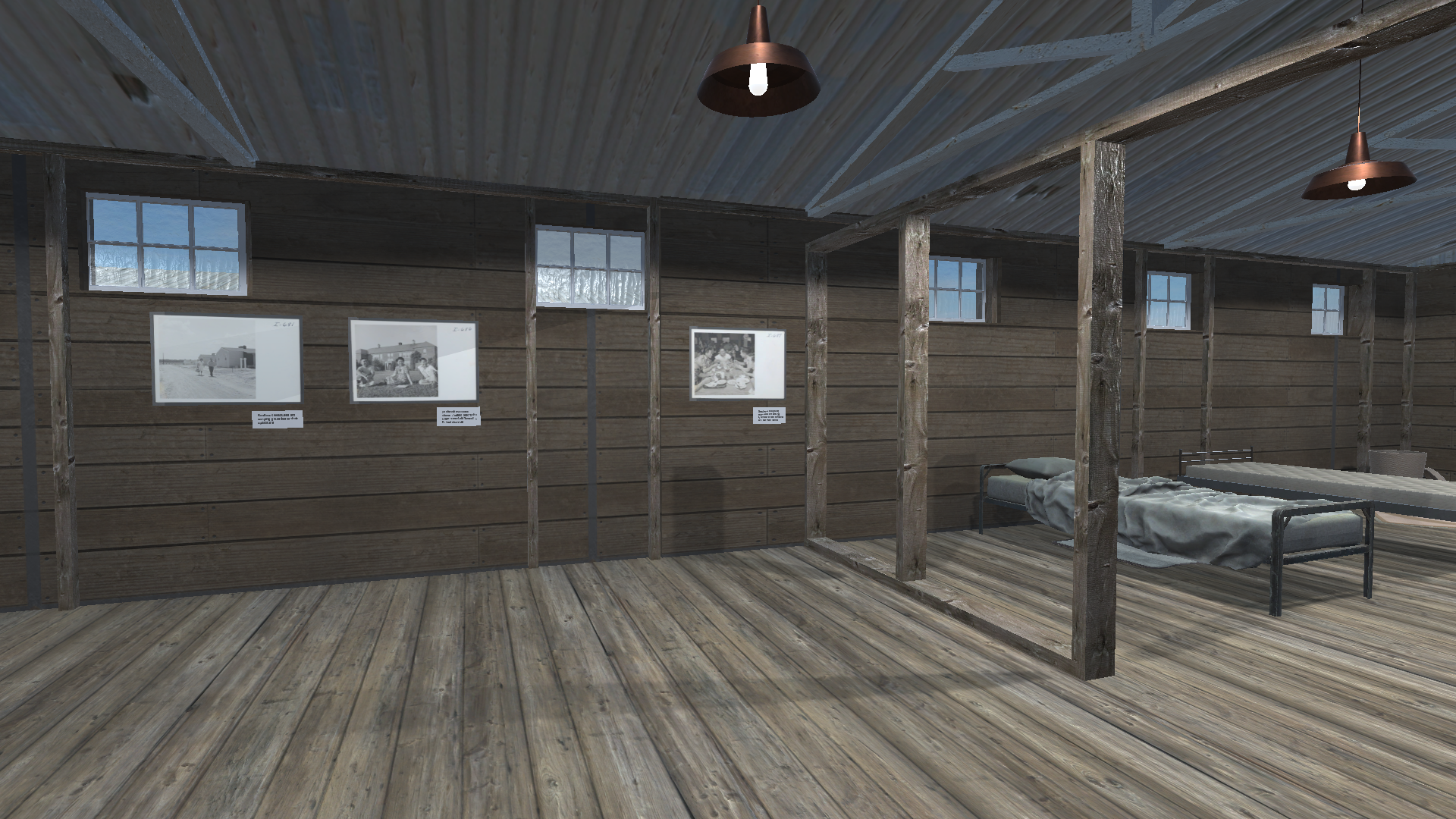

The Third Space exhibit shares stories about individuals and families who underwent these experiences, told simply through the family photos and art objects they created in that period. These artifacts convey a nuanced history of the resettlement from a local community perspective. For context and comparison, the exhibit also includes photographs taken by the WRA Photography Section during both the incarceration and resettlement. Shown opposite of family photos and art objects created within camp and during the resettlement, the exhibit juxtaposes the Japanese American community’s lived experiences with government propaganda narratives that euphemize the wartime incarceration.

This exhibit was originally planned to take place August 15 – October 4, 2020 at the Fleisher Art Memorial in South Philadelphia. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent quarantine resulted in the extended closure of this exhibition venue for the foreseeable future. While it is regrettable that the exhibit was delayed indefinitely as originally intended in a physical setting, the unexpected postponement presented an opportunity to rethink what a presentation of this topic could look like in the virtual setting. Through our collaboration with Da Vinci Art Alliance we were able to create a virtual exhibition space that would allow audiences to engage in real-time with exhibit artifacts as they might in a physical gallery setting.

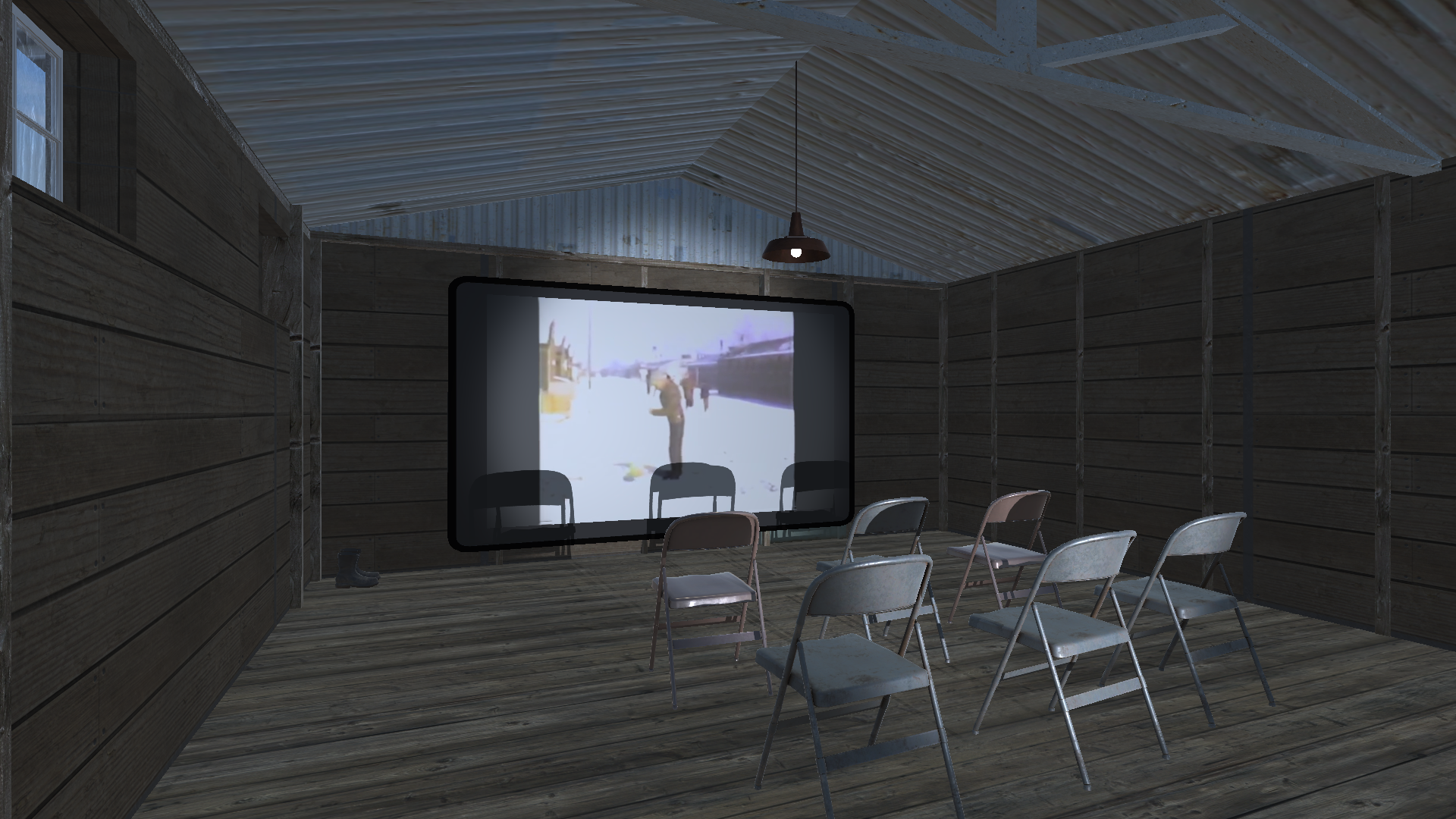

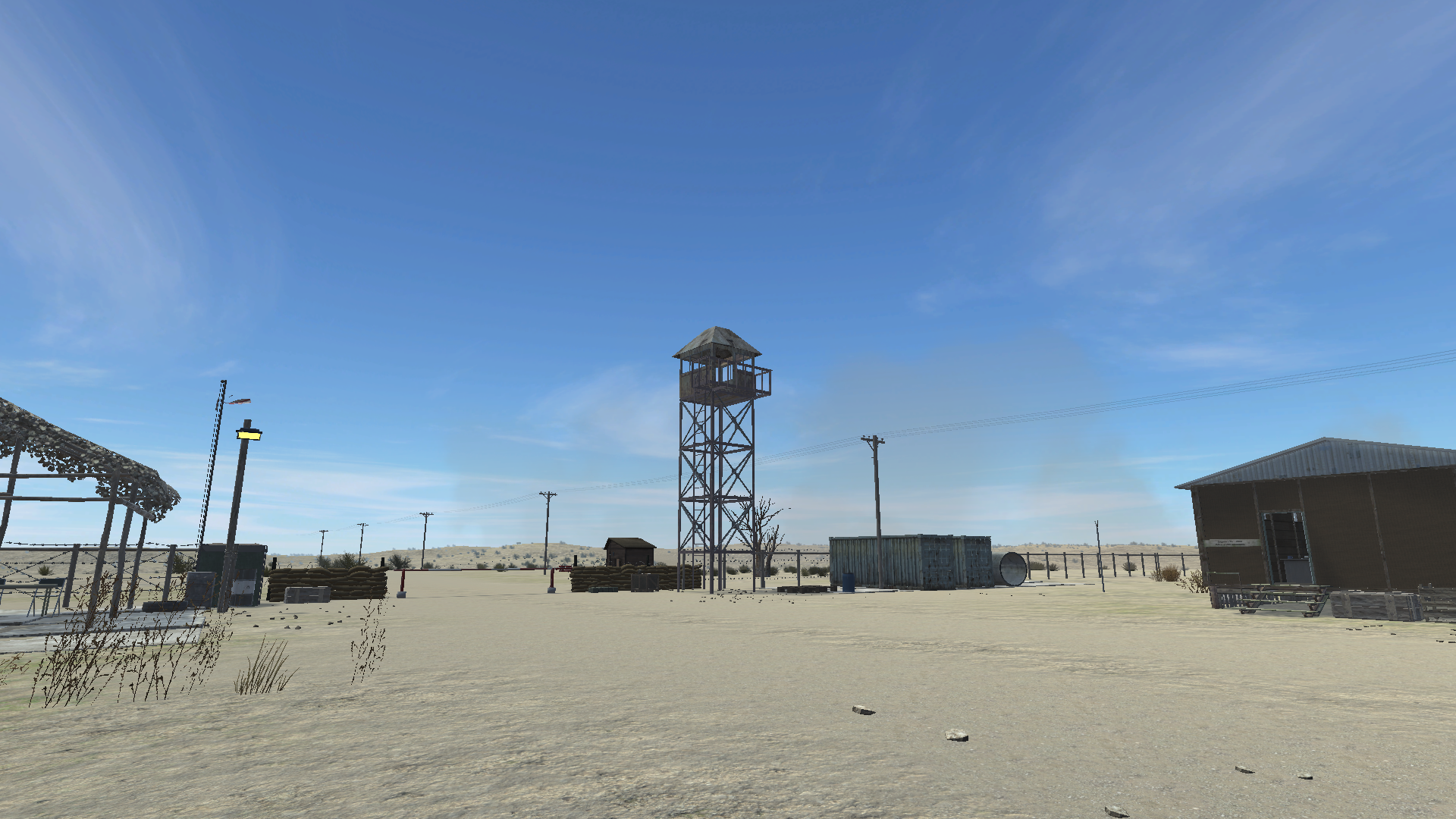

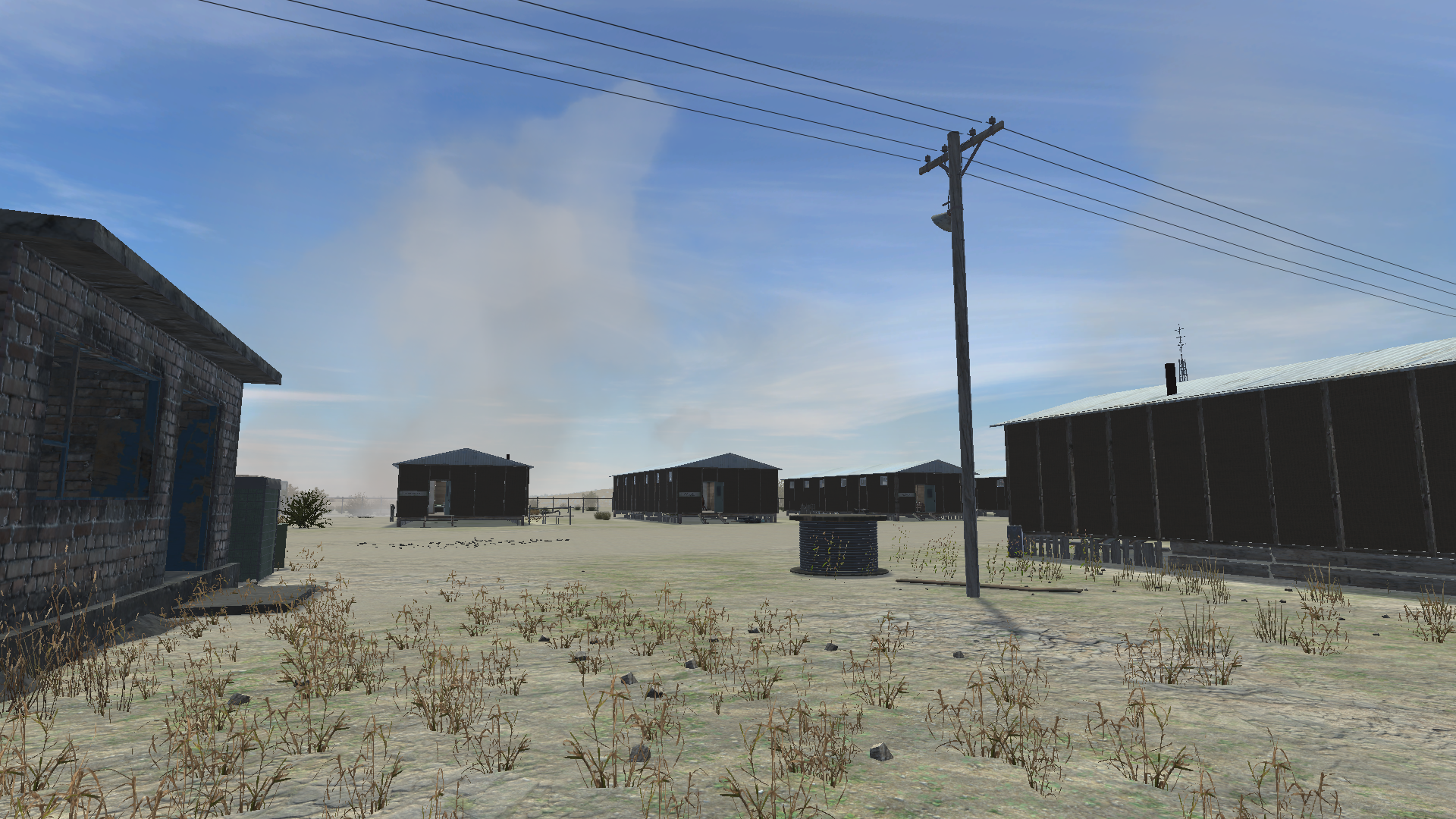

The decision to stage this exhibit within the environment of a residential camp block was not taken lightly. Our virtual exhibit space was developed through many months of collaboration with DVAA Co-Director and Exhibit Programmer Bryant Girsch, who used a video game development software called Unity to design this environment. Given the complexity of designing such a space with the limited resources available, we knew it would be impossible to create a space with total historical accuracy to the WRA camps. As such, this space is not meant to be a specific location among the WRA detention facilities. Rather it is an approximation of the aesthetic surroundings that many Japanese American community members witnessed during their incarceration ordeal. We discourage anyone from viewing this environment as a documentary equivalent of the conditions that Japanese Americans experienced in camp.

Some may find it odd that we chose this setting for an exhibition on the topic of resettlement. However, by staging our exhibit in an environment that resembles camp, we are reminding the audience that whatever successes the Japanese American community may have enjoyed in the postwar era were built on the hardships that our community endured during the wartime incarceration. Additionally, this setting is meant to evoke the lasting impacts of trauma on both incarceration survivors and their descendants, which continues to influence the community’s artistic psyche to this day.

Roy Takeno, editor, and group reading paper in front of office, Manzanar Relocation Center, Photo by Ansel Adams

Throughout the curation process this exhibit has undergone many different iterations, some that included a more extensive historical narrative than what is represented here in this final version. Ultimately, we made the decision to let the images speak for themselves, as they are perhaps the strongest testament to the realities of both wartime incarceration and the postwar resettlement. Photographers have been credited whenever possible, with original captions used in all government photographs. Other images that were crowdsourced from various Japanese American community members bear only a simple descriptive caption based on information provided.

“The Third Space” title of our exhibit has several meanings. In its most literal sense, the title refers to the physical act of resettling in a third location. We can also define the third space within the discourse of dissent as, “the space where the oppressed plot their liberation.” Given the history of Japanese American activism in the postwar era, this reading certainly rings true among the resettlement communities of Greater Philadelphia who played an active role in the Redress Movement, epitomized by local JACL leaders like Grayce Uyehara and Judge William Marutani.

From a media arts perspective, the third space can be used to reference our hybridized approach – using a virtual environment to explore historical reality, as we have in this exhibition space. In a different context, this last reading can also be used to describe the blurred lines between fact and fiction embodied by government propaganda that sought to minimize perceptions of institutional violence that Japanese Americans viscerally experienced throughout the war years and postwar resettlement. The cognitive dissonance that Japanese Americans felt amid such campaigns also resembles a third space, which they inhabited psychologically in attempting to reconcile these vastly different narratives.

Through this exhibit we hope to reframe the conversation around postwar resettlement from our local Japanese American community’s perspective, demonstrating the unique challenges associated with being a people internally displaced within our own country. In addition to telling a more complete version of this history, by reframing the resettlement as such, we hope to encourage individuals within the Japanese American community and public at-large to take a more active role in supporting current day refugee resettlement, and ending immigrant detention.

Although this exhibit may raise more questions than it does provide answers, our hope is that by bringing these community narratives into public discourse, others will be encouraged to tell their own stories. Only then will we be able to fully understand the complicated history of the postwar resettlement, and its lasting impact on our Japanese American community today.

~ Rob Buscher, Exhibit Curator and JACL Philadelphia Chapter President

Documents from Resettlement

Explore The Third Space on your own

There are two ways to explore The Third Space:

1. Download The Third Space to your computer for Mac or PC to play offline

2. Play the web version of The Third Space below.

* this version is not compatible on IOS , mobile, or Safari *

How To Navigate :

Click anywhere inside game window to the left to start

Use the W, A, S, and D keys to move forward, back, left, and right.

Move your mouse (or trackpad) to look around you.

Additional Reading:

The Third Space: Japanese American Resettlement in Greater Philadelphia is co-sponsored by Philadelphia and Seabrook Chapters of Japanese America Citizens League, in partnership with Da Vinci Art Alliance.

Researcher and Exhibit Curator: Rob Buscher

Exhibit Programmer: Bryant Girsch

Funders:

Japanese American Citizens League Legacy Fund

National Park Service Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant

Photography Credits:

Ansel Adams (camp photos – barracks 2-L), WRA Photography Section

Justin L. Chiu (Seabrook resettler art – barracks 5-R)

Dorothea Lange (camp photos – barracks 2-L), WRA Photography Section

Hikaru Iwasaki (camp and resettlement photos – barracks 2-L, 3-L, 4-L), WRA Photography Section

Bill Manbo (camp photos – barracks 2-R), courtesy of Takao Bill Manbo

Toyo Miyatake (camp photos – barracks 2-R), courtesy of Alan Miyatake

Jack Muro (camp photos – barracks 2-R), courtesy of Japanese American National Museum

Yoshio Okumoto (camp photos – barracks 2-R), courtesy of Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation

Video Credits:

Dave Tatsuno (Topaz footage – barracks 1-R), courtesy of the Tatsuno Family

Office of War Information (Japanese Relocation excerpt – barracks 1-L), Library of Congress

Artwork Credits:

George Nakashima (Woodwork)

Masatada Ikeda (Watercolor)

Kiyo Tsutsumida Nojima (Tsumami canvas)

Matsugoro Yoshida (Watercolor)

Additional Community Photographs Sourced By:

Gerald Kita

Ed Kobayashi

Miyo Moriuchi

Margret Mukai

Mira Nakashima

Masaru Ed Nakawatase

Ellen Kitagawa Shapiro

Trevor Taniguchi

Paul Uyehara

Special Thanks:

Michael Asada, JACL EDC Governor and Seabrook Chapter

Beverly Carr, Seabrook Educational and Cultural Center

Jamie Hendricks, Japanese American National Museum

Jarrod Markman, Da Vinci Art Alliance

Eric Muller, University of North Carolina

Mira Nakashima, George Nakashima Foundation for Peace

Dakota Russell, Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation

Gerard Silva, Fleisher Art Memorial

Natasha Varner, Densho